Towards the implosion of NATO?

Origins of NATO (1949)

NATO is a political and military alliance created in 1949, in the aftermath of the Second World War, at the instigation of the Americans. It pursued three main goals: containing the Soviet Union by stationing U.S. forces in Europe, reining in German power after two devastating world wars, and fostering the political and economic integration of Western Europe under close U.S. ties.

Lord Ismay, NATO’s first Secretary General, famously summed it up:

‘To keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.’

Halford Mackinder

This worldview drew heavily from the geopolitical ideas of British geographer Halford Mackinder (1861-1947), which shaped maritime powers’ strategy—first Britain’s, then America’s—from the early 20th century onward.

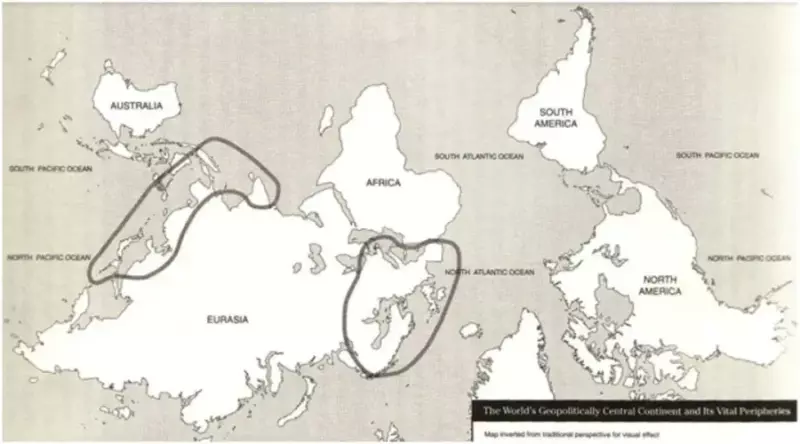

According to his ‘Heartland Theory’, the key to world domination lies in the Eurasian Heartland: a vast continental area centred on European Russia, Western Siberia and Central Asia (see map below).

This geographical area is protected from maritime powers by its strategic depth and abundance of resources. Mackinder considered Eastern Europe – Poland, the Baltic States, Ukraine, Belarus and the Balkans – not as the periphery of Europe, but as the ‘gateway’ to this Heartland.

His famous dictum: “Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; who rules the World-Island commands the world.”

The Anglo-Saxons have thus always feared a German-Russian alliance, which would combine German industrial and technological power with Russia's immense resources and strategic depth, directly threatening their supremacy based on control of the seas.

Through NATO, the United States sought to bring West Germany closer to its sphere of influence while limiting the expansion of the Soviet Union.

A major shift for the US

For the United States, forging a permanent military alliance with Europe in 1949 marked a dramatic break from tradition. Until then, America had stuck to sporadic interventions and avoided long-term overseas commitments.

This approach followed the isolationist tradition of the United States, inherited from the Monroe Doctrine. It was inspired by Washington and Jefferson's warnings against ‘permanent alliances,’ which risked dragging the country into foreign wars far removed from its vital interests.

From then on, Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty obliged Washington to consider any attack on one of its allies as an attack on itself. That pledge led to a lasting U.S. military footprint in Europe: bases, forward-deployed troops, nuclear weapons, and a fully integrated command.

A fruitful alliance

The transatlantic alliance established the United States as a global power, responsible for defending ‘the free world’ against the Soviet Union. At the time, their economy accounted for nearly 50% of global GDP and half of industrial production. They also held two-thirds of the world's gold reserves and, thanks to the Bretton Woods agreements (1944), the dollar became the international reserve currency.

Throughout the Cold War, this alliance was an undeniable success. It ensured relative stability in Europe, laid the foundations for Franco-German rapprochement and enabled the emergence of the European Union, while generating unprecedented prosperity.

Lack of clear purpose and American hubris (1991)

After the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991 and the Warsaw Pact’s dissolution, NATO lost its original adversary—and its core reason for existing. A few observers and diplomats, then in the minority, believed that the Alliance should have been dissolved. In reality, the debate focused less on its disappearance than on its transformation and possible eastward enlargement.

The debate on NATO's transformation and enlargement

George F. Kennan, the architect of containment, called NATO enlargement a “fatal mistake.”In his view, such a policy would revive Russian nationalism, hinder the country's democratisation and recreate a climate of Cold War. He argued that any enlargement was guided by ideological optimism. He warned that such an approach neglected the geopolitical, historical and psychological realities of the post-Soviet space.

Bill Clinton, who was in office from 1993 to 2001, took the opposite view, pushing for expansion so NATO could anchor a “Europe whole and free.” It would fill the security vacuum left by the end of the USSR and stabilise the young democracies of Central and Eastern Europe. The Alliance would cease to be a defensive structure and would instead promote Western values.

American ambiguities

US Secretary of State James Baker told Mikhail Gorbachev in February 1990 that the Alliance would not move ‘one inch eastward’ if the USSR agreed to the accession of a unified Germany to NATO.

Assurances were also given by George H. W. Bush, Helmut Kohl and François Mitterrand, as evidenced by declassified documents from American, Russian, British and German archives.

But these commitments were never formalised in a treaty. For the Americans, they were to be interpreted as temporary guarantees, linked to the circumstances of German reunification.

The Hubris of U.S. Unipolarity

After the collapse of the Soviet bloc, the United States accounted for approximately 20 to 22% of global GDP in terms of purchasing power parity, as well as approximately 20 to 25% of global industrial production. The dollar remained the undisputed reserve currency. Washington's grip on international institutions — the UN, IMF, World Bank — was hegemonic.

American supremacy was based on its military power, financial dominance, technological advances and cultural influence, driven by Silicon Valley and Hollywood. American elites were convinced that liberal democracy and free markets would lock in their dominance forever, and that globalization would make great-power rivalry obsolete.

Francis Fukuyama's thesis on the ‘end of history’ embodied this optimism. The conviction that the world was about to converge towards the Western model, summarised in two principles: democracy and the market economy.

Imperial levies and structural weaknesses

However, the United States, an ardent defender of free trade, was already showing signs of profound structural weaknesses. The country was moving away from the classic imperial model—based on industrial power and technological efficiency—and sliding towards a service-based and financialised economy. Its productive apparatus was massively relocated, and its growth increasingly depended on externally financed debt.

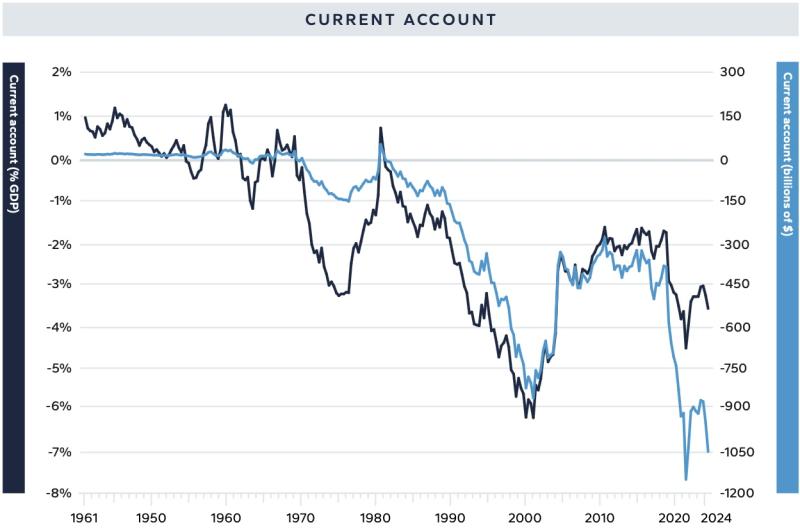

America thus shifted from being a manufacturing empire to a consumer empire in relation to the rest of the world, as illustrated by the sharp deterioration in its current account in the 1990s (see chart below).

The dollar, as the world's reserve currency, allowed Wall Street to absorb a growing share of global savings. But these massive capital account surpluses were in fact only the counterpart to a permanent trade deficit.

The strength of the dollar, by making American exports more expensive, hurt the competitiveness of the country's producers and accelerated its deindustrialisation.

The United States' ability to live beyond its means, financed by the rest of the world, has been described by Emmanuel Todd as an ‘imperial levy’. The system rested on two pillars: dollar hegemony and the implicit threat of U.S. military power.

Imperial machinery and economic crisis (2008)

The Bucharest Summit

At the NATO summit in Bucharest in April 2008, a historic decision with tragic consequences was taken: the promise of future integration of Ukraine and Georgia into the Atlantic Alliance. This was despite the reluctance of France and Germany, who were aware of the risk of exacerbating tensions with Moscow.

The decision came amid already mounting tensions with Moscow. A year earlier, at the Munich Security Conference, Vladimir Putin had delivered a virulent speech criticising the international order dominated by the United States.

He condemned the “illegitimate” and destabilizing unipolar order dominated by Washington. He accused the US of violating international law and resorting to unilateral force, referring to the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Above all, he warned that NATO's expansion eastwards was perceived by Moscow as an existential threat.

Brzezinski's thesis

The possibility of Ukraine joining NATO is often presented by American politicians as the right of a free and sovereign state to choose its alliances. But this argument obscures a geopolitical reality that is well known in Washington.

Zbigniew Brzezinski, one of the most influential American strategists of the 20th century, explicitly stated this in 1997 in The Grand Chessboard, updating Halford Mackinder's principles:

"Without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be a Eurasian empire. With Ukraine — subordinated and then integrated — Russia automatically becomes an empire again."

For Brzezinski, Ukraine is a key piece of Russian power. With its 50 million inhabitants, it combines heavy industry, some of the most fertile agricultural land in Europe and strategic energy infrastructure.

Geopolitically, it opens up a natural corridor to Central Europe and the Black Sea, giving Russia strategic depth vis-à-vis NATO.

Kiev is also the cradle of medieval Russia. Its loss would be much more than a territorial setback: it would carry a major symbolic and identity-related burden.

Finally, Ukraine itself determines the balance of power in Eurasia. Oriented towards the West, it helps to push Russia back towards Asia in the long term. Integrated into Russia's sphere of influence, on the other hand, it allows for the reconstitution of a geopolitical entity capable of challenging American hegemony on the Eurasian continent.

Enlargement One Step Too Far

From Moscow’s perspective, each wave of NATO enlargement represented a steady military creep toward Russia’s historic borders.

In 1999, the first post-Cold War wave brought in Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic. In 2004, seven new states joined the Alliance: the three Baltic countries — Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania — as well as Bulgaria, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia, all former members of the Warsaw Pact.

In 2008, the prospect of Ukraine and Georgia joining the Alliance in the future was seen by Moscow as a breaking point. While Russia never demanded the dissolution of NATO, it repeatedly denounced its expansion, insisting that Ukraine's accession would pose an existential threat.

The 2008 economic crisis

A few months after the Bucharest summit, the subprime crisis hit the United States with the spectacular bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers on 15 September. This global crisis was the result of the bursting of a real estate bubble fuelled by massive debt.

Total US debt (households, businesses, the financial sector and the government) rose from around $1 trillion in 1964 to more than $50 trillion in 2008, a fifty-fold increase.

This explosion of credit, a source of unprecedented wealth in the United States and around the world, was made possible by the end of the Bretton Woods agreements in 1971. Since then, money and credit creation have no longer been constrained by gold reserves, then set at $35 per ounce.

In 2008, when the private sector began to default, threatening to cause a global depression, the US government intervened aggressively. It stimulated public spending, causing the budget deficit to explode, and financed government bonds through money creation.

The worst financial crisis since the Great Depression—exposing America’s mountain of debt—was ultimately “solved” by transferring private-sector debt onto the public balance sheet through even larger government borrowing.

Originating on Wall Street, this crisis also revealed the vulnerability of emerging countries, which are dependent both on exports to the United States and on a dollar-centred financial system. China and Russia, which were hit hard, responded by stimulating domestic growth, diversifying their trading partners and gradually reducing their dependence on the dollar. These measures reflect their top priority: preserving their sovereignty.

The Western-dominated international financial institutions (IMF, World Bank) are unable to manage the crisis and include emerging countries. In response, the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China) held their first summit in Yekaterinburg on 16 June 2009, creating a forum for a multipolar order.

From 2008 onwards, central banks around the world became net buyers of gold, a trend that accelerated after 2022 following the seizure of Russian assets by Western countries.

Imperial spiral: military expansion and financialisation

The year 2008 marked a historic turning point. On the one hand, NATO continued its push eastwards, despite the disappearance of the Soviet threat nearly two decades earlier. On the other hand, the American economic system revealed its structural weaknesses, with debt becoming the main driver of its growth.

Military expansion and the financialisation of the American economy are two sides of the same imperialist coin: on the one hand, military, with the expansion of its security influence; on the other, monetary, with the dominance of the dollar as the main tool for financing American deficits. This spiral compensates for domestic deindustrialisation through external projection.

To prevent any attempt at de-dollarisation, the United States uses force against countries seeking to sell their oil in another currency, as in Iraq, where Saddam Hussein was executed in 2006, or in Libya, with the assassination of Muammar Gaddafi in 2011.

Towards the disintegration of the Atlantic Alliance? (2026)

NATO's defeat in Ukraine

On January 15, 2026, President Trump told Reuters that Ukraine—not Russia—was blocking a potential peace deal. But how did we get to this point?

After undermining European strategic stability by gradually moving its forces closer to Russia's borders, Washington exerted decisive influence over Ukraine following a coup d'état in 2014.

The aim was to bring the country into the Euro-Atlantic orbit by accelerating its militarisation, in defiance of Moscow's repeated red lines.

After Russia launched its ‘special military operation’ in February 2022, the United States responded by providing massive military, financial and political support to Kiev. This strategy was accompanied by the most severe international sanctions ever imposed, mobilising the G7 in an attempt to destabilise the world's third largest geopolitical power.

Despite the scale of these measures, the war of attrition between Russia and NATO, with Ukraine caught in the middle, seems to be inexorably turning to Moscow's advantage, due to its superiority in human, logistical and industrial resources.

Nord Stream

The United States has gone so far as to sabotage major energy infrastructure linking Russia to Germany — the Nord Stream gas pipelines — as revealed by journalist Seymour Hersh, and as evidenced by the irony displayed by US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent when discussing the subject with Tucker Carlson (see below).

This is the largest terrorist act on European soil since World War II. These pipelines belonged to both the Russian state and European partners, i.e. NATO members. Rarely mentioned publicly, this act has most likely undermined trust within the alliance.

American disengagement

Realizing they couldn’t “bring Russia to its knees,” Washington is now positioning itself as a mediator in a conflict it helped ignite. This stance contrasts with the increasingly bellicose attitude of European and Ukrainian allies, even though the balance of power on the ground is unfavourable to them.

The latest Pentagon report now seems to relegate Russia to the status of a ‘persistent but manageable’ threat, placing it outside the core of US strategic priorities. This strategic shift confirms a refocusing of the United States towards other theatres deemed more decisive.

Europeans are thus being encouraged to ‘shoulder a greater share of the burden’, which translates into both a gradual disengagement by Washington and increased pressure on the European Union to increase its military spending, to the benefit of the American defence industry.

Responsible for the most serious conflict in Europe since the Second World War, which caused millions of deaths and displaced persons, Washington can nevertheless count on the Europeans to obscure their own responsibilities and failures, and thus present itself as a reasonable power, driven by the pursuit of peace.

Greenland and the diplomatic crisis

On 6 January 2026, a few days after the kidnapping of the Venezuelan president, Donald Trump provoked a diplomatic crisis by announcing his intention to annex Greenland, by agreement or by force, in order to ‘secure’ the Arctic against China and Russia.

He threatened to impose tariffs ranging from 10% to 25% on the eight European countries that refused to sign an agreement. After dragging NATO into a lost war against Russia, Washington was now threatening its own allies, emptying Article 5 of its substance and, with it, the very foundation of the Alliance.

In response, the French president dispatched a symbolic contingent to Greenland, accompanied by German, Scandinavian and British units, so as not to give in to American blackmail. Trump went so far as to threaten the French president, claiming that he would have ‘only a few months left in power’ and brandishing the prospect of tariffs of up to 200% against France.

On 21 January 2026, Trump made a spectacular about-turn at the Davos Economic Forum. In his speech, he explicitly ruled out the use of force and announced that he was in the process of concluding an agreement on Greenland and the entire Arctic region.

Even though the military and economic escalation has been defused, the damage has been done. Europeans' trust in the United States has been deeply shaken. Threatening tariffs and even territorial annexation against a fellow NATO member has badly shaken European trust in U.S. reliability.

A note by analyst George Saravelos, head of currency research at Deutsche Bank, published on 18 January, caused quite a stir. In it, he points out that Europe holds more than $8 trillion in US assets (debt and equities), almost double the rest of the world combined.

According to him, in the event of a prolonged escalation, the EU is not powerless against the United States. A reduction in its investments could reveal the structural vulnerability of an American economy dependent on foreign capital.

A few days later, at the same Davos Forum, Ray Dalio, founder of the world's largest hedge fund, confirmed Saravelos' intuition. He pointed out that economic wars often evolve from a ‘trade war’ — as is currently the case with customs duties — to a ‘capital war,’ involving capital controls, investment restrictions or massive asset sales.

Scott Bessent, US Treasury Secretary, played down the risk of a massive sale of US bonds by Europe, saying he had contacted the CEO of Deutsche Bank, who reportedly distanced himself from his analyst's rating.

However, the key message remains: the US economy relies heavily on imports of manufactured goods from the rest of the world, financed by foreign capital that fills its deficits.

‘America First’ and the return to the Monroe Doctrine (2026)

Despite Donald Trump's aggressive and often spectacular rhetoric, the reality is stark: the American empire, which dominated unrivalled after the collapse of the Soviet bloc, is in decline.

The model that had prevailed for three decades — importing manufactured goods on a massive scale, financing them with foreign capital flows, and threatening any country that attempted to break free from the dollar with military force — is coming to an end.

With his ‘America First’ doctrine, Trump is, beneath the apparent chaos, executing a strategic retreat. He is pulling the empire back into the Western Hemisphere, attempting to reindustrialise the country and imposing American interests, openly defying international law.

The world is beginning to realise that Washington has suffered its first military defeat in Ukraine, even if European warmongering and the stubbornness of its leaders in ignoring reality still allow the United States to be presented as a peaceful intermediary in this conflict.

The diplomatic crisis over Greenland has profoundly shaken Europeans' confidence in Washington's erratic and aggressive leadership. All the alliances established since 1945 are now on hold.

Washington increasingly blurs the line between allies and adversaries and dismisses multilateralism as overly constraining. While NATO has not yet been officially dissolved, its core — Article 5 and the guarantee of mutual protection — is already dead.

By reaffirming ‘America First’, Trump is explicitly reviving the fundamental principles of the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, modernised under the name ‘Trump Corollary’ in the 2026 National Defence Strategy. He is refocusing American priorities on the national territory and the American continent, asserting an exclusive sphere of influence vis-à-vis China and Russia.

Official Pentagon strategy documents confirm this: priority is then given to the Indo-Pacific (against China), to the management of Iran (and the protection of Israel), and only then to the Russian question — largely left to the Europeans.

Even if NATO continues on paper, its original meaning and mutual trust have been hollowed out. The rupture has already happened—only neither side has fully admitted it yet.

«Towards the implosion of NATO?»