Review of the Parliamentary Elections in Moldova

Introduction

Due to its location and history, the Republic of Moldova plays a key role for the West in supporting Ukraine and in its strategy against Russia. NATO and the EU are extremely sensitive to the political situation in this small country in southeastern Europe.

There are essentially three Moldovas: the Republic of Moldova, the Republic of Transnistria—which seceded from Moldova in the early 1990s following the collapse of the Soviet Union and has since aligned itself with Russia—and all Moldovans who do not live in the two aforementioned states. Citizens who do not live in Moldova itself represent a third of the total Moldovan population and thus have considerable influence in elections.

We drew attention to the volatile situation in and around Moldova early on in several articles, see here, here, here. The elections that have taken place in recent years have exacerbated the situation in the country rather than easing it.

Some demographic facts

Imagine you are a citizen of a country with a total population of 3.6 million people, 30 percent of whom live abroad, i.e., 1.2 million. That is the reality in the Republic of Moldova.

2.4 million people currently live in the country itself. That is 13.6 percent less than in 2014. In relation to Germany, that would be a decline of about 11 million people.

Moldova is divided into 32 counties, three independent cities, and the Autonomous Territorial Unit of Gagauzia. Since 2014, 28 administrative regions of the country have seen a population decline of more than 20 percent. The largest declines were in the following regions:

· Ocnita: minus 29.5 percent

· Leova: minus 29.2 percent

· Briceni: minus 28.7 percent

· Cantemir: minus 28.5 percent

Statistically speaking, Moldova lost these citizens to other countries. The only region that has seen population growth compared to 2014 is the capital Chişinău: plus 16.8 percent.

In national elections, all voters living abroad are also entitled to participate in the election. In the case of Moldova, this is a decisive factor in the election.

According to information from MIDEI – Moldova's Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Integration – the 1.2 million Moldovans living abroad are distributed as follows:

country | Moldovans living abroad in thousands |

Russia | 350 |

Italy | 250 |

France | 130 |

Germany | 100 |

USA | 60 |

Great Britain | 42 |

Ukraine | 24 |

Romania | 19 |

362 |

Foreign citizens of a country are strongly influenced by the circumstances in which they live, because they have consciously chosen their country of residence and, in some cases, left their home country under difficult circumstances and not entirely of their own free will.

This is the background against which the Moldovan government's activities to organize the participation of Moldovans abroad in the elections must be assessed. The Moldovan government was well aware of these facts and made appropriate organizational decisions.

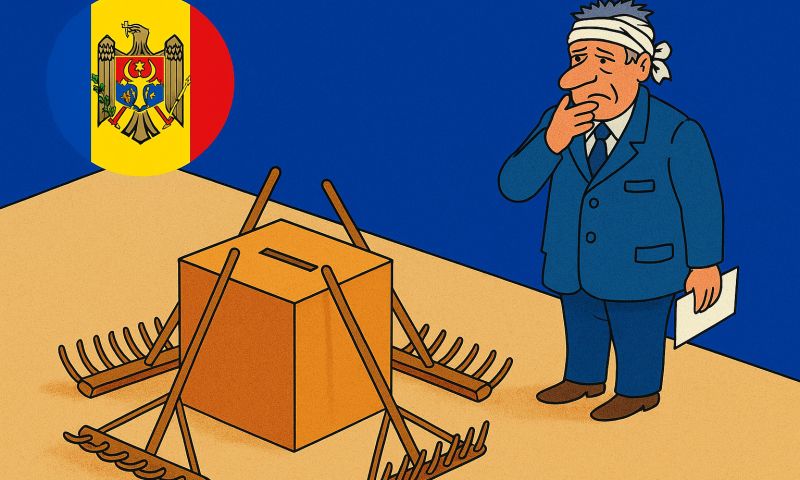

The elections under Sandu

Since Maia Sandu won her first presidency in 2020, no national election has been conducted correctly and without suspicion of manipulation. This applies to all elections, including her presidential elections in 2020 and, even more so, in 2024.

Sandu and her administration clearly gained a wealth of experience in the process and visibly and tangibly incorporated this into the parliamentary elections on September 28, 2025, in order to rule out any unwanted surprises.

The starting point for all considerations was the ruling PAS party's justified fear of losing its majority in the domestic parliament. So the government decided to steer the election results of the diaspora in the desired direction.

This led to rigorous administrative decisions that turned the election into a farce in parts. The result not only made Sandu rejoice, but also found the desired resonance in the Western media.

The Tagesschau news program can be quoted here as an example:

The relief in Chişinău, Brussels, and elsewhere was based on the fact that the ruling PAS party achieved a total of 50.20 percent of the votes cast.

The obvious manipulation of the Moldovan parliamentary elections

In Moldova itself, Sandu's PAS party achieved the following overall result:

Votes cast: 1,300,759

Of which for the PAS: 44.13 percent

As Sandu suspected, it was therefore up to the diaspora to decide the outcome. And it did not disappoint. Let's look at the figures:

country | Moldovans living abroad in thousands | Number of polling stations | Votes cast | Voter turnout in % | Result for PAS in % |

Russia | 350 | 2 | 4.109 | 1,2 | 11,66 |

Italy | 250 | 75 | 80.103 | 32,0 | 77,68 |

France | 130 | 26 | 25.488 | 19,6 | 76,94 |

Germany | 100 | 36 | 38.012 | 38,0 | 75,79 |

USA | 60 | 23 | 10.607 | 17,7 | 88,63 |

Great Britain | 42 | 24 | 27.434 | 65,3 | 83,69 |

Ukraine | 24 | 2 | 612 | 2,6 | 78,76 |

Rumania | 19 | 23 | 29.209 | 153,7 | 88,12 |

362 | 12 | 12.017 | 3,3 | 29,89 |

The election results listed in the table are taken from the official results published by the Central Election Commission.

Anyone with a little numerical understanding and life experience will easily notice a few anomalies that are difficult to explain on their own. The mystery is solved by the measures taken by the government and the Central Election Commission. The following is an incomplete list:

The number of polling stations in the diaspora countries that posed the greatest threat to the government was drastically reduced. For example, there were only two polling stations in Moscow for Russia. Furthermore, only 10,000 ballots were made available at these stations. Nevertheless, there were long lines in front of the polling stations. It therefore took some administrative effort to reduce voter turnout to just 1.2 percent.

A total of 12 polling stations were opened for Transnistria, three times fewer than in the last presidential elections in fall 2024. These were all located in Moldova and not in Transnistria. In addition, the day before the election, the election commission announced that some of these polling stations had suddenly been moved further inland. Just as suddenly, there were major roadworks on the roads leading to the polling stations, which were difficult to drive around. Those who made it that far had already passed the checkpoints on the Dniester bridges connecting Transnistria with Moldova. The police carried out thorough checks there, which took up to three hours per vehicle. Then, during the course of the election day, when the lines of cars on the bridges made it clear that many citizens from Transnistria still intended to exercise their right to vote, the bridges were completely closed. First because of construction work, then because of alleged warnings that the bridges had been mined. Mine clearance was then scheduled to begin after 10 p.m., long after the polling stations had closed.

The planting of mines at polling stations—exclusively those set up for voters from Transnistria—was also part of the plan, as was a selective shortage of ballot papers.

The Moldovan police were also successful. They reported the arrest of three citizens from Transnistria who had placed a cardboard box with the unmistakable inscription “Dynamite” in a clearly visible spot in the trunk of their vehicle.

As expected, voter turnout in Russia and Transnistria reached historic lows. Ironically, this happened in countries where Maia Sandu's ruling PAS party had no chance of winning, but had to fear losing its majority in parliament as a result of a fair election result.

The situation was quite different in Romania, however, where a phenomenal turnout of 153.7 percent was recorded. There are several explanations for this. On the one hand, Moldovans can also exercise their right to vote abroad. In the last presidential elections, for example, Romanian citizen and Moldovan President Maia Sandu did so herself, attracting considerable media attention. Secondly, there were numerous reports that many people had voted multiple times at different polling stations in a kind of carousel system.

President Sandu also made her own personal contribution, repeatedly addressing the electorate on election day, contrary to all the rules, to demand that they make the “right choice.” She publicly threatened to annul the elections in the event of an incorrect result. An election result that did not declare the ruling PAS party the winner would be a clear sign of a “Georgian scenario.” According to Sandu, Tbilisi trampled on European values and deprived its people of the chance of a future in the EU. She therefore demanded that people either vote for the ruling PAS party or face the prospect of becoming a “Russian colony.”

In the autonomous region of Gagauzia in the south of the country, there was ultimately an overwhelming vote of 82.35 percent for Sandu's fiercest opponent, the Patriotic Bloc party. Maia Sandu's party achieved just 3.19 percent there. This result came about despite repeated system failures throughout the election day in Gagauzia. Computers suddenly froze, preventing staff at polling stations from identifying voters and issuing ballots. Surprisingly, there were no such problems in other regions.

There was also blatant election fraud: in the village of Baurci, a young 18-year-old woman was voting for the first time. There she learned that she had already cast her vote in the capital Chişinău, 130 km away. However, the woman's family strongly denied this.

A bizarre incident occurred in Moscow in connection with the elections in Moldova. The Russian FSB arrested an employee of the Moldovan secret service SIS. The Moldova Mare party, which was participating in the elections, claimed that the FSB confiscated two bags of ballots that had been pre-filled for the ruling PAS party.

It remains unclear whether Moldova Mare's claim is true. However, the fact is that shortly after this claim was made, Moldova Mare was excluded from the election by the Central Election Commission – on the day of the election itself. An incredible example of “democratic fairness,” respect for democratic rules and laws, respect for the electorate, and thus respect for the voice of the people. But that is not the end of the Moldova Mare chapter. The Central Election Commission instructed that the votes cast for the party so far be redistributed to the ruling PAS party, Maia Sandu's party.

Cristina Vulpe, representative of the Victory Block party participating in the election, said she had voted “for freedom of thought and democracy in practice, not on paper.” Her colleague Vadim Grozavu called the election campaign “the dirtiest and most undemocratic in the country's history.”

There was a huge spread in the results within Moldova. While the PAS won 58.62 percent of the vote in the capital, as already mentioned, only 3.19 percent voted for them in Gagauzia. This is a reflection of a deeply divided country.

As a result of all the “creative measures” taken, the elections narrowly produced the result hoped for by President Sandu and expected by the EU – a narrow majority of 50.2 percent.

In their statements, the Moldovan government and the EU repeatedly referred to the role of the diaspora in deciding the election. As the facts and figures make clear, it was by no means the diaspora alone. It was the selective measures taken against the most influential diaspora groups in Russia and Transnistria that prevented them from participating in the election as normal. These measures, which made a mockery of democracy, kept Maia Sandu's party in power and thus preserved Moldova as a bridgehead for the EU against Russia.

Moldova after the parliamentary elections is Moldova before the local elections

The government and the Central Election Commission are not wasting any time and are continuing to clean up the political environment in Moldova. Immediately after the elections, the Central Election Commission restricted the political activities of three parties for twelve months. According to Pavel Postica, deputy chairman of the Central Election Commission, this “restriction” includes a ban on participating in elections and referendums. It affects the parties “Moldova Mare,” “Heart of the Republic of Moldova,” and “Modern Democratic Party.” All this without a court order.

With these decisions taken immediately after the parliamentary elections, Moldova's political leadership is preparing the ground for the local elections that will take place on November 16, 2025. This approach is part of the consolidation of the political party spectrum that has been taking place in Moldova for several years. It is worth recalling here the conviction of the leader of Gagauzia, Elena Guzul, to seven years in prison on the basis of unproven charges.

A ban on the activities of parties that took part in the parliamentary elections on September 28, 2025, will inevitably have an impact on the outcome of those elections. The question arises as to how these parties can continue to operate and what should happen to the votes cast for them. This raises the question of the legitimacy of the elected parliament.

In order to provide a democratic framework for the decisions of the Central Election Commission, on October 6, 2025, at the request of the Central Election Commission, the Constitutional Court of Moldova will rule on the legality of the parliamentary elections held on September 28, 2025. Part of the “bargaining chip” before the court is also specifically the legality or illegality of transferring votes from one party to another, as envisaged by the Central Election Commission and already practiced on election day.

What is not obvious is also important in this case. President Maia Sandu is in her second term. The Moldovan constitution does not provide for a third term. This would require a constitutional amendment. However, despite all the election manipulations, the ruling PAS party simply does not have enough votes in parliament to achieve this. The chairman of the “Democracy at Home” party, Vasile Kostjuk, believes that all the current processes are aimed at securing as many votes as possible for the ruling PAS party in a seemingly democratic manner, in order to enable Maia Sandu to serve a third term in the wake of a constitutional amendment.

Conclusion

What significance did the parliamentary elections in Moldova have for observers from a European perspective? Elections in Moldova have become almost traditionally undemocratic. They thus confirmed a Europe-wide trend. Elections are no longer about competition between different political directions and possibilities. From France to Moldova, the aim is to keep parties and individuals installed and deemed suitable by the democratically illegitimate EU leadership and the circles behind it in power by any means necessary, under the guise of democratic processes. It is equally about using democratically embellished institutions such as election commissions, courts, and the powers of the legislature and executive to nip political alternatives in the bud. This pattern can be seen in France, for example, against Marie Le Pen, in Germany in the case of the BSW or the AfD after the last federal election, or the annulment of a government formation in Thuringia on the “instructions” of Chancellor Merkel years ago, and in Romania with the annulment of an entire election.

Is there a way back?

«Review of the Parliamentary Elections in Moldova»