Le Xinjiang derrière les gros titres

La Bombe de l'Arrivée : Un Choc pour les Occidentaux Conditionnés

Après avoir atterri à Ürümqi, la capitale de la région autonome ouïghoure du Xinjiang (communément appelée Xinjiang), il est immédiatement apparu que les Ouïghours, une minorité musulmane de langue turcique, considèrent cet endroit comme leur foyer.

En sortant du hall des arrivées, j'ai remarqué une enseigne de restaurant sur laquelle était écrit « EGG BOMB » (Bombe d'Œuf).

Le nom suggère avec esprit que le Xinjiang préférerait être connu pour ses « bombes culinaires » que pour les explosifs terroristes qui ont autrefois frappé la région et le reste de la Chine, comme le illustre ce titre :

Alors que la soi-disant guerre contre le terrorisme menée par les États-Unis a coûté la vie à d'innombrables civils innocents, les médias occidentaux ont réagi avec indignation aux efforts antiterroristes de la Chine, allant d'allégations de génocide culturel à des violations physiques des droits humains. Le double standard ne pourrait être plus évident.

Pourtant, alors que les gros titres brossaient un tableau sombre, la réalité sur le terrain révélait un scénario complètement différent.

Depuis l'aéroport, j'ai pris le métro moderne pour me rendre au centre-ville, où les panneaux étaient soigneusement affichés en ouïghour, en mandarin et en anglais. À une station, trois jeunes femmes ouïghoures sont montées à bord et se sont assises en face de moi. Leurs regards curieux et leurs bavardages joyeux donnaient le sentiment d'être un témoignage de la vie quotidienne. Lorsque je leur ai demandé si je pouvais les prendre en photo, elles ont répondu non pas avec méfiance, mais avec des sourires radieux et approbateurs.

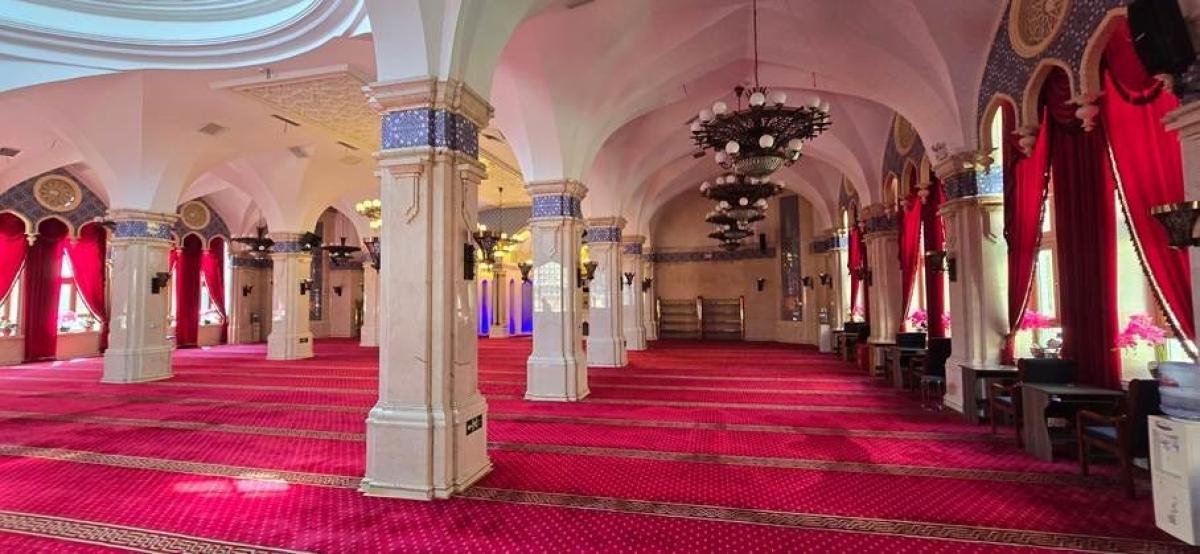

Quand l'architecture rencontre la fascination : la Grande Mosquée, un sanctuaire de silence et de splendeur

Devant la Grande Mosquée d'Ürümqi, qui peut accueillir environ 700 fidèles, j'ai rencontré une grande famille ouïghoure. Une jeune fille s'est empressée de mettre en pratique son anglais pour traduire les questions de sa famille : « D'où venez-vous ? Aimez-vous Ürümqi ? » Leur curiosité débordante et leurs rires chaleureux contrastaient magnifiquement avec l'atmosphère silencieuse et respectueuse de la mosquée derrière nous. À cet instant, j'ai senti le cœur du Xinjiang battre dans son peuple : ouvert, chaleureux et vivant.

Par respect, je n'ai pas filmé les fidèles, mais j'ai exploré l'intérieur de la mosquée lorsqu'elle était vide et que le tournage était autorisé. Les salles dégageaient une tranquillité particulière : vastes mais intimes, un espace sacré entre les prières.

Les fidèles ouïghours suivaient l'appel quotidien à la prière, un rythme de paix et de communauté.

Un moment de joie lors d'un mariage

Au cours de mon exploration, j'ai rencontré un couple ouïghour vêtu de magnifiques costumes traditionnels qui se préparait pour ses photos de mariage. La mariée rayonnait de joie, tandis que le marié semblait au départ très sérieux. Sur un coup de tête, j'ai fait un petit geste pour détendre l'atmosphère, et à ma grande joie, cela a fonctionné ! Son expression sévère s'est transformée en un rire sincère et chaleureux. Le photographe m'a également adressé un sourire reconnaissant, et ce qui aurait pu être une photo formelle est devenu un cliché empreint d'une joie pure et authentique.

Voyager en train au Xinjiang : comment les investissements et la préservation culturelle soutiennent la vie des minorités

Getting around Xinjiang often meant traveling by car or train. Many stations provided announcements in Mandarin and Uyghur, as you can hear 👉 here. For a solo foreign traveler, this was challenging but benefited the region’s main ethnic groups.

China’s language policy reflects its broader approach to minorities. Banknotes display five scripts: Mandarin, Uyghur (Arabic script), Mongolian, Tibetan, and Zhuang. In Xinjiang, education is primarily in Mandarin—the official language and mother tongue of 91% of China’s population—but Uyghur is also part of the curriculum, as is Tibetan in Tibet. Street and shop signs are generally bilingual.

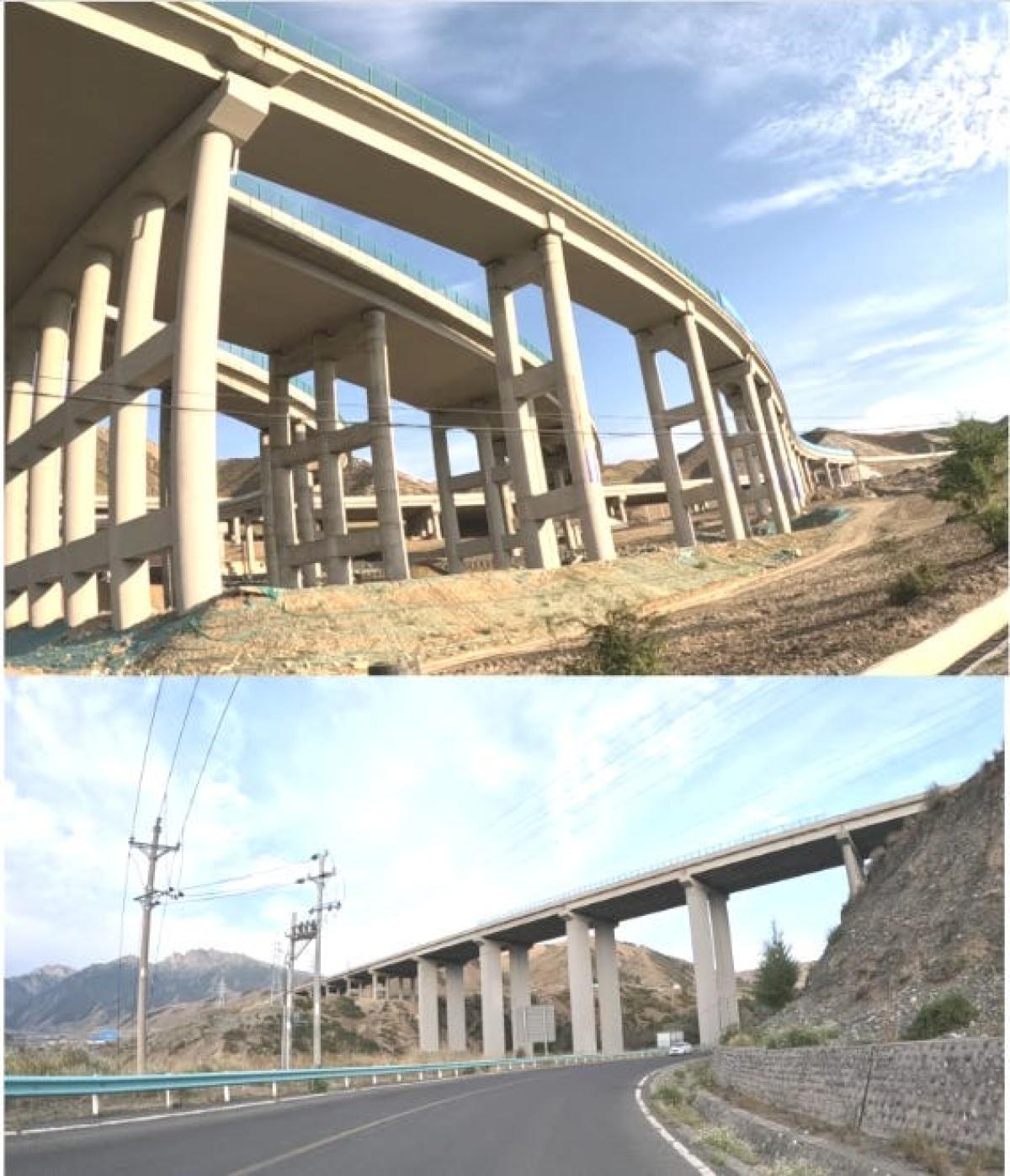

From the train window, I could observe massive investments in modern infrastructure: desert wind farms, power plants, highways, massive bridges, and an extensive power grid—all aimed at lifting millions out of poverty.

Xinjiang has been at the crossroads of the Silk Road for centuries. Its oases and mountain passes connected East Asia with Central Asia and beyond. Caravans crossing the Taklamakan Desert and the Tianshan Mountains transported not only goods but also religions, languages, and artistic traditions—leaving a lasting cultural imprint on the region.

Xinjiang’s geographical location still grants it central importance today. It borders eight countries and is a key hub of the Belt and Road Initiative. New railways and highways follow old caravan routes, reconnecting China with the world.

On one trip, I sat next to a Uyghur couple. Their Mandarin was limited, as with many Uyghurs, and my translation app didn’t support Uyghur. Yet we communicated effortlessly—through smiles, gestures, and a few shared photos.

As mentioned, train travel often felt like a real adventure. Announcements were only in Mandarin and Uyghur; English was rarely heard. Yet fellow passengers were always friendly and helpful—even when communication relied solely on gestures and smiles.

Heavenly Lake: Xinjiang’s Natural Wonder

Xinjiang is a land of extremes—from endless deserts to rugged mountain ranges that rise dramatically into the sky.

During long drives, the air conditioning struggled with the relentless heat, often exceeding 44.5°C. But as we climbed into the mountains, temperatures dropped, offering a refreshing change.

The true wonder awaited high in the mountains: the “Heavenly Lake.” Its name is literal. Deep blue waters reflect snow-capped peaks while waterfalls tumble into quiet valleys—a sight so breathtaking it seems almost mythical.

Legend has it that dragons once swam these waters—looking into its depths, one can easily imagine this story.

The shores were alive: Han Chinese and Uyghur families alike. A few Uyghur tourists asked me to take photos with them—a Western visitor. For a moment, I felt not just an observer but part of the landscape, part of the moment.

👉 A single post cannot do this place justice—soon I will release a video on my channel to capture the full beauty and magic of Heavenly Lake.

Disclaimer for the skeptical: My trip through Xinjiang was entirely independent—no government approval, no minder, all expenses self-funded. Authentic insights, not propaganda.

Youth Culture and Uyghur Cuisine

I was fascinated by the vibrant energy of young people here—they spoke animatedly in Uyghur, joked and laughed, sometimes turning everyday obstacles into playful climbing frames. Their style was a modern fusion, effortlessly blending global and Chinese fashion trends.

This contemporary spirit formed a wonderful contrast when one evening a young woman served delicious Uyghur food, lovingly prepared by her mother. Tasting this authentic home cooking became an instant highlight of my trip. While the daughter moved with the confidence of a global citizen, both she and her mother wore traditional Muslim headscarves—a graceful nod to their heritage, speaking volumes about their pride and cultural continuity.

This blend of tradition and modernity was everywhere. I met a Uyghur shop owner whose business acumen matched her cultural pride: she sold a carefully curated collection of fashionable headscarves, blending tradition with modern life.

Other shops, like the one pictured below, welcomed me with vibrant, rhythmic Uyghur music spilling onto the street—an irresistible acoustic invitation to enter.

Xinjiang’s Agricultural Wealth: Farms, Markets, and Local Pride

Xinjiang is often called China’s breadbasket—and a journey through the region makes this clear. Golden wheat and sunflower fields stretch to the horizon, vineyards produce quality wine, orchards yield nuts and fruits, and melons are said to be the sweetest in the world. Abundance is everywhere.

This fertility relies on centuries-old water management. Ingenious karez systems—gravity-fed underground channels—brought meltwater from the Tianshan Mountains to the desert. Dug by hand and linked through tunnels and wells, they carried water miles downhill directly to the fields without pumps or evaporation loss.

This heritage continues, now on a grand scale. Modern canals and massive irrigation systems run through arid lands, turning once-barren earth into seas of cotton and tomatoes. It’s a story of transformation: lush, green fields thriving in stark contrast to the desert, nourished by mountain waters.

Agriculture is changing rapidly. Cotton, once picked by hand, is now harvested by massive machines. Factories processing local products create stable, better-paying jobs, while new residential blocks and industrial facilities rise as symbols of progress under Xinjiang’s vast sky.

Yet despite modernization, the human spirit remains central to the harvest. Farmers visibly take pride in their work. A Uyghur melon farmer even placed his portrait on the packaging—a striking mark of quality and identity, carrying his name and face from the field to tables across China.

In a Uyghur fruit shop, I marveled at watermelons so massive they resembled boulders—some weighing up to 20 kilograms. As I struggled to lift one, the shopkeeper laughed, his joy matching the generosity of his produce. This simple exchange perfectly reflected the spirit of Xinjiang’s harvest.

Elsewhere in China, I have drunk cappuccinos made by robots, as shown in my video 👉 “China’s Collapse—or is the Future Already Here?” In Xinjiang, however, coffee is a ritual. Cups are buried in hot sand so the coffee brews slowly, developing its characteristic aroma and richness. Carefully poured, strong yet mild, it is more than a drink—it embodies centuries-old Uyghur hospitality, deeply rooted in desert life.

Watching the preparation, inhaling the aroma, and savoring the first sip was a small but unforgettable moment—a taste of culture that makes travel vivid and memorable.

Life in the Countryside: Kazakh and Uyghur Communities

A warm, outgoing Kazakh woman living in a wooden house amidst a community of Uyghur yurts gave me one of my most memorable encounters. Though I forgot her first name, she was known on WeChat as Miao. A Xinjiang University graduate, she spoke English and told stories of her family’s deep roots in the region. While we talked, her mother—continuing a multi-generational tradition—offered tea and local snacks, while Miao translated her mother’s Kazakh into English for me.

At home, Miao spoke Kazakh; with neighbors, she communicated effortlessly in Uyghur; with Han Chinese, she spoke Mandarin—a vivid reflection of Xinjiang’s cultural diversity. The atmosphere was one of harmonious ease. At one point, Miao and her Uyghur neighbors spontaneously started dancing. On my X account, you can see 👉 a short clip of this moment.

I don’t think it was for my sake, but they kindly let me capture the moment—a joyful and authentic expression of communal life, which I am happy to share here.

Final Thoughts: Xinjiang Beyond the Headlines

On my journey, I met many radiant Uyghurs, sometimes seemingly curious at the sight of a rare Western visitor like me. What stayed with me most was observing minority communities—Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and others—radiating pride, joy, and contentment. This contrasts sharply with the treatment of minorities elsewhere.

In Ukraine, for example, the state has imposed measures severely restricting the rights of the Russian-speaking minority: their language is largely banned, political parties forbidden, media suppressed, and churches seized. In Xinjiang, by contrast, Uyghur culture is not suppressed but actively preserved and promoted within national law and development plans. It is remarkable that many Western politicians, activists, and media who frequently make unsubstantiated claims of “genocide” in Xinjiang remain conspicuously silent about the actual cultural genocide of the Russian minority in Ukraine.

This selective outrage underscores the importance of looking beyond biased narratives. My travels around the globe have not always revealed the same spirit of harmony I experienced here, making my time in Xinjiang all the more special, uplifting, and unforgettable.

▪ ▪ ▪

Another Look at the Author’s Photo Album

(Copyright: Felix Abt)

Ürümqi is a bustling provincial capital that, like its counterparts across China, has experienced remarkable economic growth over recent decades. This progress brings shared challenges, such as traffic congestion, necessitating solutions like new bus and subway lines, which are currently planned or under construction.

In Ürümqi, most people pay for subway tickets electronically via mobile phone, though cash is still accepted. For foreign visitors, navigating the system is straightforward: ticket machines display information not only in Uyghur, as seen here, and Mandarin, but also in English, making the city slightly more welcoming to travelers.

The subway itself is undergoing transformation. The current single line will soon be supplemented by Line 2. Line 3 is already planned, and the ambitious vision foresees a ten-line network by 2030. Standing on the platform today, one can easily imagine a near future where Ürümqi’s public transport creates a larger, faster, and better-connected urban framework.

Xinjiang’s landscape is being reshaped by new bridges, tunnels, and roads. This extensive infrastructure is more than concrete and steel—it forms a strategic network designed to boost the economy, improve connectivity, and strengthen Xinjiang’s role in the Belt and Road Initiative. It is a monumental effort to overcome geographic isolation, integrate the region into the world, and promote shared prosperity under China’s “common prosperity” policy.

It’s not an ordinary döner kebab here, but the Uyghur original: Çağür Kebab (چاغۇر كاۋاپ). This is the Uyghur version of rotating grilled meat—the name literally means “rotating kebab.” Unlike the well-known sandwich döner, Çağür Kebab is almost always served on a plate.

The two friendly Uyghur men above run a mobile Çağür Kebab stand from a cleverly converted motorcycle.

I watched Uyghur farmers cultivating the same fertile oases as their ancestors, but with today’s tools. Thanks to them, the scent of melons, grapes, and apricots still lingers along the old Silk Road.

The bottles on the left contain Kelimazi, a carbonated drink made from fermented grains that helps locals endure the summer heat. This sweet-and-sour refreshment is a liquid taste of Silk Road tradition.

From sun-drenched vineyards and ancient orchards comes Xinjiang’s legendary snack mix: plump, sweet raisins, large, juicy apricots, and rich walnuts, mixed with crunchy almonds and jewel-like berries. It is timeless, energizing fuel for nomads and modern gourmets alike—a sweet and savory taste of history you can hold in your hand.

Today Xinjiang is perhaps better known internationally for cotton and tomatoes, but its reputation for grapes is historically and culturally significant. The region’s continental climate—with long, hot, sunny days, cool nights, minimal rainfall, and well-drained sandy soils—creates ideal conditions for viticulture, producing fruit with high sugar content, rich flavor, and intense aroma. Grapes have been cultivated in Xinjiang along the Silk Road for over 2,000 years.

Western winemakers, brace yourselves: Xinjiang wines are marching onto your shelves! Your only hope? Quickly persuade your governments to invent a “forced labor” story—so these bottles never see the light of your wine racks. American cotton farmers have shown the way. Who would have thought that good wine—like cotton and textiles—could suddenly become a geopolitical move? Cheers!

The value of sunflowers goes far beyond their beauty. They are versatile crops providing cooking oil, snacks, animal feed, and even biofuel. They also benefit the environment, detoxifying soil and supporting pollinators. With Xinjiang’s perfect growing conditions—abundant sunlight and significant daily temperature swings—it is ideal for these giant golden fields.

The Uyghurs have a strong drumming tradition, with the “Dap” drum being culturally the most significant due to its integral role in the revered Muqam. Other drums, like the Naghra and Dohl, complement the rich percussive landscape of Uyghur music, a vibrant expression of their cultural identity. “Muqam” is not a person; it is the name for the great classical music tradition of the Uyghur people. It can be imagined as a vast and sophisticated musical system often compared to Persian Dastgah, Azerbaijani Mugham, or Indian Raga. It is the cornerstone of Uyghur culture and one of Central Asia’s most significant musical traditions.

The sight of mostly older Uyghur women wearing headscarves is a striking reminder of profound societal changes in Xinjiang. What seems ordinary at first glance carries multiple meanings: a natural generational shift toward modern fashion; official disapproval of religious symbols like headscarves and beards—linked to past radicalism and ongoing concerns, as Uyghur militants who contributed to attempts to overthrow a secular government in Syria have threatened to return to China and commit terrorist acts; and the quiet, strategic choices of younger Uyghurs to adapt for better career opportunities. From this single detail emerges a sense of evolving identity, ongoing adaptation, and broader cultural change shaping daily life, even as the Uyghur language and much of the culture persist.

Traditional Uyghur clothing, exemplified here, is worn during festivals and major celebrations. This elegant garment, often a long, loose-fitting robe or flowing one-piece dress, is traditionally worn over trousers. Its most striking feature is the intricately embroidered neckline, which may be a standing collar or an open collar. Worn on important occasions such as Nowruz (Persian New Year), weddings, and religious holidays, the garment’s splendor reflects the deep joy and cultural significance of the event.

The Bank of China in Ürümqi proudly displays its name in Uyghur, Mandarin, and English—a small but unmistakable sign of inclusion and cultural recognition. Switzerland takes a similar approach, considering minority languages in schools, authorities, and public spaces. Ukraine, by contrast, goes the other way: signs are only allowed in Ukrainian and English, while Russian—the language of millions—is explicitly banned.

Yet many of the loudest critics of China’s “cultural genocide” in Xinjiang appear surprisingly unimpressed by the massive restrictions in Ukraine. Inclusion is noble here, exclusion forgivable there—cultural genocide seems only a matter of political convenience. Naturally, the sprawling Western anti-China ecosystem—NGOs, activists, academics, journalists—must continuously feed its machinery with new accusations and scandals. Should one expect anything else?

▪ ▪ ▪

👉 Words and photos can only convey so much. For an even more immersive journey with vivid atmosphere, watch the video on my YouTube channel.

▪ ▪ ▪

«Le Xinjiang derrière les gros titres»